The Killing of Columbus's Railroads

For more than forty-three years, Columbus, Ohio, has been left out from the nation's passenger rail network. The reasons why are complicated.

The Demolition

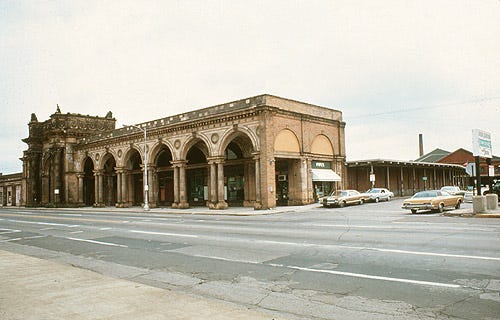

It was a Friday evening on October 22, 1976. The people of Columbus left work for their homes or a night out. Their minds might have wandered from the streets in front of them. Driving north on High Street, they would have seen it, just like it had always been: the soot-stained grand arcade of Union Station that had stood in the heart of Columbus for almost a century. The Beau Arts-style station, built in 1897 had been designed by Daniel Burnham’s firm. It towered over the High Street viaduct. Bathed in the grandeur of the previous century, it had put up a good fight against its modern surroundings.

At six o’clock, an 82-ton crane’s claw bucket owned by S.G. Loewendick & Sons tore into the arcade’s side.1 Clyde Tipton, president of the Battelle Commons Corporation, looked on. Battelle intended to build the Ohio Center on the train station’s twenty-seven-acre lot.2 A crowd formed along High Street, including members of the Ohio Historical Society who had heard from Tipton less than two weeks prior that “there were no immediate plans for demolition.”3 Ralph Loewendick, president of S.G. Loewendick & Sons, told the Dispatch “the arcade’s demolition had always been part of the [plan], as far as he knew.” The arcade was on the Federal Register of Historical Buildings, putting its demolition on legally dubious grounds.4 The Historical Society’s Franklin Conaway, trustee and urban affairs consultant, and Judy Kitchen, Historic Preservation Office administrator, struggled to get in contact with anyone who could stop it. It was Friday night; no one was in the office. They finally managed to contact the attorney C. William Brownfield at four o’clock the next afternoon, who in turn got a restraining order signed by the county’s Common Pleas Judge, George Tyack, in his own home at five forty-five. Rushing back to the demolition site, Brownfield handed a Loewendick supervisor the restraining order twenty-four hours after work began.5 The delay meant that, by that point, all the restraining order was protecting was mostly a pile of rubble. Preservationists and the demolition team decided that the main arch of the arcade, at that point still standing, would be preserved and moved, but demolition would continue.6 The main portion of Union Station—the platforms, waiting rooms, train sheds—would begin to be demolished in April 1977.7

The plan put forward by Battelle for the Ohio Center included a much smaller replacement station. The entire complex was predicted to be complete in two-and-a-half years after Union Station’s demolition was finished.8 In the meantime passenger service would continue. A train came twice a day on Amtrak’s National Limited line between New York and Kansas City. Before the Ohio Center’s station could be completed, service was run out of the “Amshack,” a sheet-metal, prefabricated barn on the side of the tracks.9 Then, on September 30, 1979, Supreme Court Justice Warren Burger permitted Amtrak to cut unprofitable long-distance lines, including the National Limited. The final train came through Columbus at 7:25 the following morning, bound for Kansas City. One of the passengers was the 87-year-old Margaret Wettroth. At her age, and with her health, she was not able to take buses or planes, nor could she drive. She took the train once a year from her home in St. Louis to New York, to visit her granddaughter. She told a Dispatch reporter, “I’m not very well and the station in New York is close to where my granddaughter lives. I guess I won’t be able to see my granddaughter anymore.” Mrs. Wettroth wept.10

The City and its Station

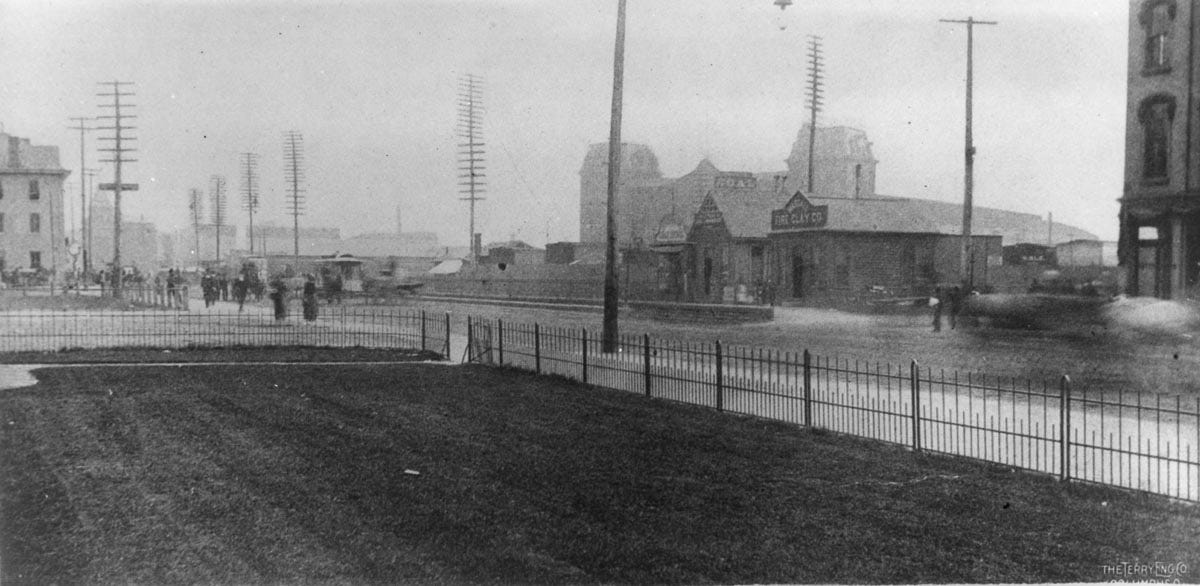

The history of railroads in Columbus began in 1850, as a train of the Columbus & Xenia Railroad rolled to a stop in a makeshift station in Franklinton, across the Scioto from the city’s downtown. By the end of the year, the C & X had completed its bridge across the river leading into a gigantic wooden barn half a mile beyond.11 This new station lay at the corner northeast corner of High Street and Naghten (now Nationwide Boulevard), where there would continue to be a train yard for the next 126 years.12 By the next year, the Cleveland, Columbus & Cincinnati began running service between the three cities through the same three-track barn used by the C & X, making it the very first union station in the world.13 In the following two decades, yet more companies began running service into Union Depot (“Depot” and “Station” seem to have been used interchangeably) connecting Columbus to Indiana, Wheeling, Pittsburgh, and Athens.14 It was perhaps the connection to Athens, in 1870 that contributed the most to the beginning of Columbus’s industrial economy.15 Southeast Ohio’s timber, iron, natural gas, and coal, flowed north to Columbus, and the return trip to Athens carried Columbus-made mining equipment, steel, furniture, and wagons.16

As more railroads came to Columbus, the large wooden barn grew inadequate and, by 1868, the several railroads operating out of the station incorporated the Columbus Union Depot Company.17 In 1875, its work on the second Union Station was complete. The new eight-platform structure hosted forty-two trains per day, operated by five rail companies, but the high volume again began to be an issue. The tracks coming out of the west side of the building had still been crossing High Street directly, with many-ton trains sharing right-of-way with pedestrians and horses.18 With the choice of routing High Street over, under, or through the tracks, Columbus chose all three options at once. The width of High Street was split between a wooden viaduct, a tunnel, and an at-grade crossing.19

By 1893, the number of trains coming in and out of Columbus had more than doubled to 118 per day. The next year, the city approved plans to construct a suitable replacement, and by 1897, the third and final Union Station was completed. Construction involved the addition of a proper viaduct over the tracks and an expanded trainshed (the part of a station the trains actually stop in, at platforms) of the second Union Depot. The High Street viaduct spanned the full width of the station’s tracks, unlike previous solutions.20 The arcade—the one torn down in 1976—was built on the edge of the viaduct and led down to the trainshed below.

In the first half of the twentieth century, Union Station and its satellite freight yards, maintenance facilities, and warehouses had a gargantuan footprint on the map of Columbus. Union Station proper lay on the rough square enclosed by High Street in the west, Naghten in the south, Swan in the north, and Fourth in the east. This is the twenty-seven-acre plot on which Battelle would build the convention center. But there was much more. Between Fourth and Cleveland Avenue, massive warehouses fanned off from the tracks. Crossing under Cleveland, the Pennsylvania Railroad built its Yard B.21 To the west of Union Station lay the Pennsylvania’s other freight depot, Spruce Street Yard, as well as several other companies’ smaller yards, strewn across the corridor through which I-670 now runs.22

In 1950, Union Station and its related yards and warehouses employed 11,378 workers (over seven percent of the city’s workforce).23 At their height, railroads were central to Columbus’s economy, and Columbus was central to the railroads. The Pennsylvania Railroad’s second-largest maintenance facility was in Columbus, as were all of the Hocking Valley Railroad’s offices. Manufacturing dedicated to the railroads represented some of the city’s most notable firms. Buckeye Steel Castings, which produced knuckle couplers (the metal ‘fists’ that couple together to link train cars) and the Columbus Rolling Mill, that at one time produced 100 tons of rails per day.24 All of this industry was fundamentally reliant on the presence of Union Station and the other freight yards, deep within Columbus’s downtown.

The Decline

In 1930, an all-time peak average of 164 trains—passenger and freight—would pass through the city of Columbus daily. In the same year, about 1.7 million motor vehicles were registered in Ohio.25 Around this time, Ohio’s Department of Highways and Public Works studied the state’s entire road network, surveying road quality and motor-vehicle traffic. Along the 5,221 miles of roadway receiving 600 or more vehicles per day, about half were still gravel or dirt.26 Even on state highways, widths varied from ten to fifty feet, but were predominantly twelve to eighteen feet wide, or, about a lane to a lane-and-a-half, by modern standards.27 As a result, about three quarters of all motor-vehicle traffic made trips of less than sixty miles.28 It was the very peak of the period when trains held a seemingly insurmountable position. The 1930s were the decade of the Art Deco, stainless-steel streamliners. Racing through dirt-road cities of tightly packed, nineteenth-century buildings, these locomotives must have seemed to have dropped down from outer space. Next to a Model T, they were aesthetically incomparable.

But something changed. Within only twenty-six years, the number of trains through Columbus would fall to forty-six per day.29 Between 1930 and 1956, the number of motor vehicles registered in the state roughly doubled to 3.7 million. That same year, 1956, President Eisenhower signed the Federal-Aid Highway Act, accelerating highway construction begun under the New Deal.30 Within three years, Ohio began construction of I-70 and I-71 and, by 1963, I-70 was complete as an innerbelt of Columbus and work crews on I-71 were approaching the outskirts of Cleveland and Cincinnati.31 The Outerbelt of I-270 required more time, but would be completed in 1975.32 As a network, the freeways would enable not only a rapid growth of the suburbs, but likewise the relocation of manufacturing out of city centers into new, modern facilities built for truck shipping. Although not shrinking outright like Cleveland or Cincinnati, Columbus’s share of Franklin County’s population fell from 75% in 1950 to 65% in 1970.33

For railroads, inherently operating out of static, centrally located passenger and freight yards, as the center of gravity of both people and businesses moved out of cities, this meant the permanent loss of potential customers. Once a family is in the suburbs, why ride a train to Cleveland when it could be faster, cheaper, and easier to drive? Or, once a factory nestles itself along the Outerbelt, how might it even ship by rail in the first place? Before the highways, in 1930, Franklin County had 11,295 inhabitants employed directly by the railroads. By 1960, that number had fallen to 5,086. And, by 1990, that category of occupation was not even included in the census. In the same span, as the county’s population tripled, the number of workers in trucking, warehousing, and “other transportation” multiplied tenfold, from 2,299 in 1930 to 20,259 in 1990.34

In the postwar decades, trucking tore into railroads’ share of the freight market. The improvement of the highways enabled trucks to become larger and faster, and their trailers to lengthen. As the American economy soared in its strongest period of growth, rail freight revenues were static. Instead, nearly all of this growth went to trucking. Intercity freight revenues hauled by trucks doubled in the 1950s, most of this growth coming from high-value, low-weight goods. By 1963, other than, ironically, automobiles, most manufactured goods were transported by truck, not train.35

If freight revenues were bad enough, passenger revenues were eyewatering. Between 1951 and 1957 alone, the two major railroads in the region, the Pennsylvania Railroad and the New York Central, saw passenger revenues fall by 15% and 25%, respectively.36 Even after spending years attempting to win back passengers with new cars and more luxurious amenities, passenger lines continued hemorrhaging money. The New York Central particularly tried to remedy the situation, combining lines and decreasing service on the those remaining, but passenger trains continued to lose riders. The Central concluded that their once-famous long-haul “named lines,” carrying monikers like Twentieth Century Limited, Ohio State Limited, the Commodore Vanderbilt, were simply no longer viable. Passenger service had to be scaled back and restricted to shuttles between single, close pairs of major cities. On December 2, 1967, the New York Central slashed almost all the named lines, including the Ohio State, connecting New York to Cincinnati via Columbus and Cleveland.37

In an effort to stay alive, the Pennsylvania and the New York Central merged, forming Penn Central on February 1, 1968. Since the two companies’ networks lay practically on top of each other, their merger could eliminate redundant yards, tracks, and trains in a part of the country that was increasingly relying less on the railroad.38 Columbus, a perfect example of this redundancy with its massive Pennsylvania and Central freight yards downtown, would see these combined into one gigantic, automated facility, that would become known as Buckeye Yard. Buckeye moved Penn Central’s operations out of the city proper and into the suburbs of Columbus, with better access to the highways and much more space to expand.39 It would have been the largest freight yard in the Penn Central system, second only to Selkirk, in New York. Would have been. Loyalties to the Pennsylvania and the New York Central remained strong throughout Penn Central, and, since Buckeye’s planning came from the Central side, Pennsylvania loyalists dragged their heels. Buckeye Yard was built, and was used, but not as effectively as it could have been.40 In 1970, only its third year of existence, Penn Central was losing $1 million a day ($7.68 million in 2022). Not two months after someone unknown leaked that number, the railroad’s creditors slammed the brakes and the company entered receivership, becoming the largest corporation in the world to declare bankruptcy, on June 21, 1970.41 Two years into its bankruptcy and needing any liquidity that could be coughed up, Penn Central was approached by a group from a little town, far out on the other side of the Appalachians. They were interested in buying one of Penn Central’s properties, a decrepit old station they barely even used anymore, and they wanted it for $6 million ($43 million in 2022). That group was called the Convention Center Building Commission. That property was called Union Station.42

Battelle

In 1918, John Gordon Battelle died. He had spent his life amassing an iron and steel empire based in Columbus, leaving it to his son, Gordon.43 Then, when Gordon Battelle passed away only five years later, half his wealth was willed toward the creation of a nonprofit research company: Battelle Memorial Institute, or simply, Battelle.44 In 1969, state and county officials realized that Battelle, by now a wealthy research and development firm benefitting from tax exemption and significant government funding, had been neglecting its obligation to donate any of its profits. Over the next six years, Battelle was forced to revoke its tax-exempt status, pay millions in back taxes, and set aside $80 million ($443 million in 2022) for philanthropic projects across the city.45 In order to handle its obligation, Battelle established the Battelle Commons Corporation, headed by its new president, Clyde Raymond Tipton Jr.46

Elsewhere in the city, the same year the state’s prosecution of Battelle began, a group of some of Columbus’s biggest businessmen began pushing the city to construct a convention center downtown. The group had not selected any particular location for construction, only specifying that it ought to be placed somewhere along High Street, north of Broad. Mayor Sensenbrenner, however, who was absolutely elated by the plan, made it clear he wanted the convention center built on the plot of Union Station.47 Sensenbrenner offered his own ideas for the center, too—maybe a big mall, or a new sports arena.48

This group of local businessmen, variously called the Downtown Area Committee, the Ohio Center Commission, or the Convention Center Building Commission, was chaired by Will Hellerman, who moonlit as the vice president of Nationwide Insurance. He was joined by several others, including the head of the Columbus Jaycees, the vice president of Huntington National Bank, and a subdistrict director of the United Steelworkers.49

Within three years of first pressing for the project, Columbus had raised a $6 million bond issue and the Convention Center Building Commission had managed to buy Union Station from Penn Central but, after that, little else happened. That is, until the Battelle Commons Corporation arrived in 1974, putting up nearly half of the $80 million it was ordered to spend. Clyde Tipton, a metallurgical engineer and PR man with no real estate development experience, was now in charge. The original plans for the convention center that called for 302,000 square feet of exhibition hall were already about halved to 158,000 square feet. Under Tipton, that would be slashed down to 60,000 square feet—less than a fifth of the original size. While demolition and removal were still ongoing, Battelle axed the transportation center earlier promised to replace Union Station; the National Limited could not look forward to moving back out of the “Amshack.” Construction would not begin on the Ohio Center until February 3, 1978, almost sixteen months after demolition started. That same month, Clyde Tipton retired from the project.50

From the day the Ohio Center opened in 1980, there were considerable problems. It was already tiny compared to the convention centers of cities much smaller than Columbus. There were not enough restrooms, businesses in its forty-four-store mall kept failing. Plans were almost immediately drawn up to expand on the complex, but it was difficult; as small as the Ohio Center was, it had not been designed to easily be connected to by further expansions. Nonetheless, by the end of the decade, the impressively named New World Center was ready to be constructed out of the side of the Ohio Center, needing only funding. It even had a famous architect, Peter Eisenman.51 By 1993, the expansion was complete (its name changed to the current, much less ostentatious, Greater Columbus Convention Center), and, since the latest addition in 2001, the entire complex has grown to 1.7 million square feet.52

Amtrak

On May 1, 1971, Amtrak began service.53 In its first two years of operation, it did not own a single mile of track, nor any stations, yards, or repair facilities. It didn’t even own any trains. Instead, it had to rely on leasing infrastructure and machinery from private railroads— railroads like the terminally ill Penn Central. To fund Amtrak, the federal government subsidized it with $3.38 billion between 1971 through 1978. Amtrak’s public relations were quick to remind the reader in a 1978 report that, from 1921 to 1976, all levels of government had paid roughly $457 billion to build and maintain roadways and, “since 1925, government assistance in the development of airways and airports [had] totaled $40.9 billion.” It also noted that “no major passenger system in the world earns a profit, although individual routes within a few systems do.”54 In 1978, Amtrak was funded with $500 million, but Britain’s passenger network was given $728 million, France’s with $930 million, and Japan’s $4.1 billion.55 Inheriting the leftovers tossed off by the private railroads, Amtrak’s greatest weakness was a shortage of, of all things, passenger cars. Between 1972 and 1977, its fleet expanded from 1,569 cars to 2,048; the ratio between miles of track per passenger car available fell from 14.66 miles per car to 13.18. For context, around the same time, other countries’ passenger rail networks often had a ratio of one-and-a-half to two cars per mile.56 This shortage had obvious consequences for Amtrak’s ability to even let people ride trains. In 1979 alone, 1.6 million would-be riders were turned down at the station for lack of room aboard trains. If someone wanted to call in beforehand to reserve a ticket, it could be even worse; in just the month of June 1979, 6 million callers attempting to purchase tickets ahead were met with busy phone lines.57

One Amtrak electrician in Billings, Montana, who had worked on the railroads for thirty years was interviewed by the Washington Post in December 1979. He told the reporter horror stories of the lack of funding, but also gross mismanagement, of the passenger system—stories that he alone had seen. On one occasion, in the middle of winter, the heating systems on one train were completely broken. “I went to the platform in Billings and told people that just about every toilet was frozen solid,” he said. “They still got on—and a lot of them were elderly people. Just imagine what our ridership figures would have looked like with thawed toilets.” On another occasion, Amtrak had underestimated how much food would be needed for a run of the Hiawatha from Chicago to Seattle. His wife had to drive to one of the stations on its route with $100 of her own money in groceries.58

Amtrak had tried, of course, to lobby for more funding, but none came—at least, never enough to ever solve its fundamental issues. And, when the Carter administration came in, it made itself clear that Amtrak had to shrink to fit the budget it was given. As the same Washington Post article explains, President Carter told the nation, “‘Trains represent the future and not the past in American transportation. I recommend this type of trip to every American.’ Having made this recommendation, President Carter continued to support legislation… that would cut Amtrak’s schedules by 43 percent.” The legislation in question prevented almost any means local authorities had to prevent Amtrak from cutting lines it deemed too dysfunctional to keep. When, late in 1979, the National Limited’s number came up to be discontinued, one congressman and the city of Dayton sued for a restraining order, failed, appealed, and succeeded. “Within hours, however, Amtrak had managed to scramble Chief Justice Warren Burger out of a weekend and onto the bench, where he promptly overruled the appeals court.59

ORTA

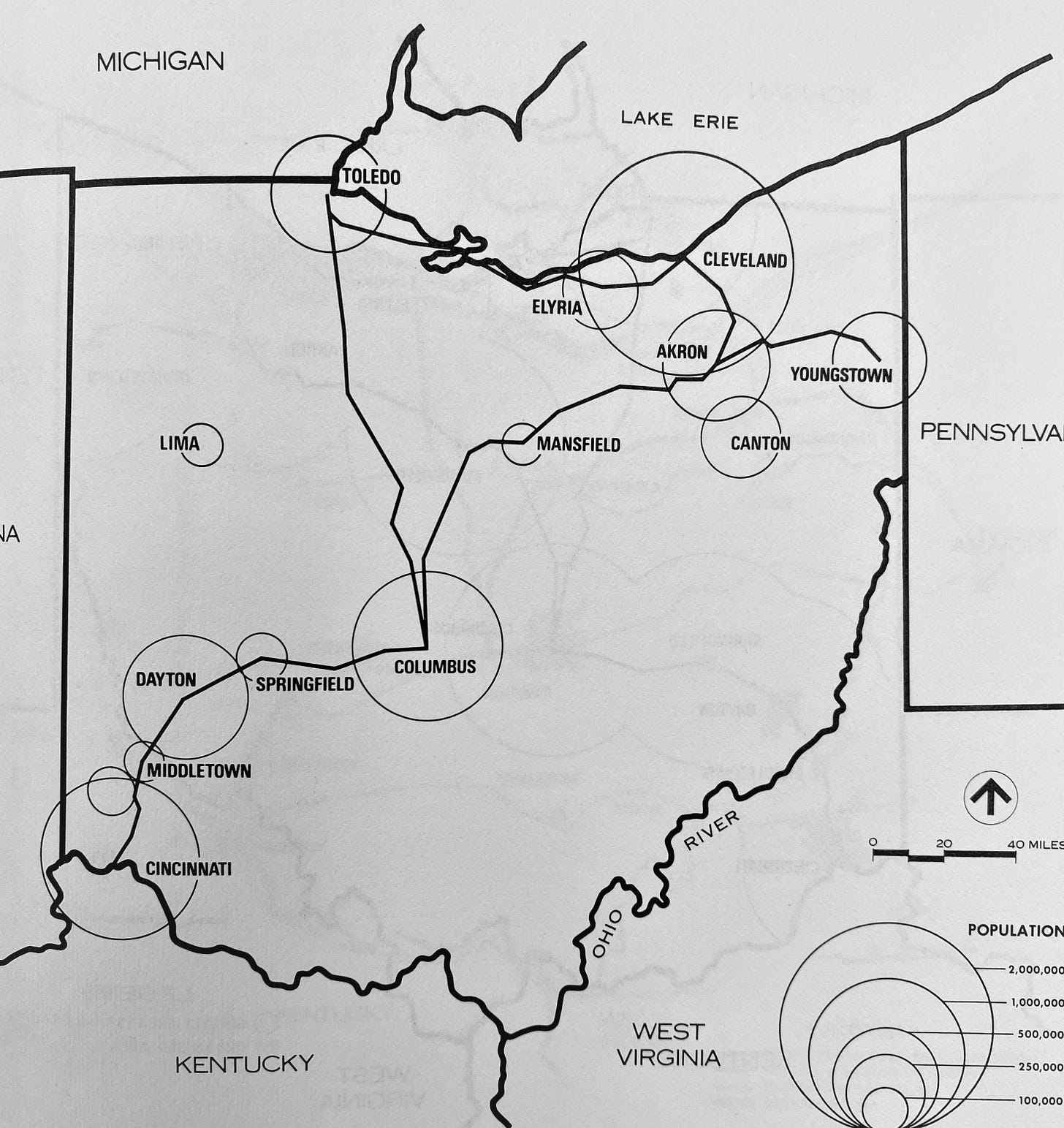

Before the demise of the National Limited, five Amtrak lines ran through Ohio at one time or another, but not one of these lines ran north-to-south.60 A passenger traveling from Cincinnati eastward to Columbus would need first to ride to Indianapolis, then into Columbus. Going from Columbus to Cleveland, a traveler would have to go first to Pittsburgh, then from Pittsburgh to Chicago, then all the way back to Cleveland.61 Using the highway, the drive from Cincinnati to Columbus to Cleveland is about 250 miles; in a train, it would have been just under 1,300 miles, crossing nine state lines across five states. Before the formation of Amtrak, this had not at all been the case. The New York Central’s Ohio State Limited was the final named line of any company to connect Cincinnati to New York City, through Columbus and Cleveland, being included in the Central’s 1967 cuts.62 The New York Central and its successor, the Penn Central, appear to have run drastically reduced service between the three Ohioan cities.63 Precisely when service between Cincinnati, Columbus, and Cleveland was cancelled is unclear, but by the first day of Amtrak’s existence, no trains ran that line.64

For eleven years, the Ohio Rail Transportation Authority (ORTA) attempted to fix this problem. As the old Union Station’s lot lay bare, late in 1977, ORTA published a technical report, entitled the Ohio High Speed Intercity Rail Passenger Plan. In it, ORTA described its study into the feasibility of a network of passenger lines joining together the corridor of Cincinnati, Dayton, Columbus, Akron, and Cleveland, with branches connecting Columbus and Cleveland to Toledo, and Akron to Youngstown.65 A year later, ORTA published its Ohio Rail Plan 1978-79. The several-hundred-page report outlined planning and statistics for the state’s entire rail network of both passenger and freight trains, and the high-speed intercity plan announced a year prior was right at the front. The Rail Plan was eager to get the construction in motion, foreseeing another spike in energy prices after the first oil crisis and severe highway congestion.66

Washington was much less enthusiastic. Eleven months after ORTA’s first release about the high-speed rail plan, a November 1978 report from the Comptroller General to Congress doubted the worth and feasibility of high-speed service outside of Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor, considering “the prospects for profitable railroad corridors outside the Northeast [to be] bleak.” Instead of expanding the national passenger network at all, the report advocated for cutting government subsidies to Amtrak, targeting its unprofitable lines to be cut.67 And, of the eleven lines designated as “highly unprofitable,” three ran through Ohio: Washington to Kansas City, New York to Kansas City—both of which stopped in Columbus—and Washington to Cincinnati. Combined, these three lines earned Amtrak $6.8 million while costing $25.1 million ($33.3 million and $123.2 million in 2022).68

On April 3 and 4, 1979, the House Subcommittee on Transportation and Commerce held hearings on ten resolutions determining Amtrak’s fiscal authorization for 1980 and the restructuring of its network. Called as a witness, ORTA’s executive director, Nat Simons Jr., urged the subcommittee to reexamine a particular bill, HR 3064. To ease the funding of cooperative transit projects between Amtrak and state and local authorities—such as a high-speed network in Ohio, for instance—the bill would have required only 20% of the total costs be supported by the latter, while appropriating funds to cover Amtrak’s 80%.69 As Simons testified, the bill had already been stuck in the House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce for two weeks. It had been introduced on March 19, 1979, by Representative Donald Pease, a Democrat, of Ohio’s Thirteenth District, which includes Youngstown. HR 3064 was cosponsored by two Republicans and twelve other Democrats, including an Albert Gore Jr. of Tennessee, but there appear to have been no further actions taken on it.70 ORTA went yet further, asking that HR 3064 be also amended to mandate Amtrak as a non-for-profit, sidestepping the entire discussion on which lines to cut and which to keep.71 This, perhaps unsurprisingly, came to nothing. A year later, the two men in charge of the hearings, Committee Chairman Harley Staggers and Subcommittee Chairman James Florio would form what became the Staggers Rail Act, deregulating the railroad-freight industry and depressing shipping rates companies could charge.72 The idea of investing in a state-owned, resource intensive high-speed rail project, and renouncing Amtrak’s obligation to turn a profit to help pay for it would have cut entirely against the momentum of Congress.

The actual focus of the hearings—not this ORTA sideshow—was for Amtrak to slash some 12,000 miles from its national 27,500-mile system. From May 1978 to January 1979, as the Comptroller General had been laying out the argument for a scale-down of Amtrak, the United States Department of Transportation compiled and published the report used by the subcommittee to inform its decisions. The department’s plan called for the cancelation of, just within Ohio, the National Limited, the Shenandoah, and the Cardinal, as well as a portion of the Broadway Limited. This would mean the loss of passenger rail service to Athens, Crestline, Canton, Dayton, Chillicothe, Dennison, Cincinnati, Hamilton, Columbus, and Lima. Only the relatively profitable line along Lake Erie would remain. The process of compiling the report also appears to have been somewhat rushed by the end, with ORTA protesting that, for the last 3,000-some miles included to be cut, the Department of Transportation did not provide space for public input on the reductions.73

By the end of 1979, Amtrak would indeed cut around a third of its network. The federal government would not be of use. The Carter administration’s DOT was pursuing a project of transportation deregulation.74 Congress would not, and Amtrak could not, help ORTA. Still, the Ohio Rail Transportation Administration bore on with its plan. In 1983, ORTA published the Ohio State Rail Plan Update 1982-83, and again, right at the front of the report was the high-speed plan. In it, ORTA estimated that, with current technology, the proposed network could reach top speeds of 150 miles an hour on new, purpose-built, grade-separated track. That way, it would not have to share track with slow freight traffic, unlike Amtrak.75 ORTA also scrapped its plan to use diesel or diesel-electric locomotives, as it had imagined in the original vision, opting for a fully electrified system.76 The network to be constructed by Ohio had also expanded to link to neighboring states, many of whom had their own local high-speed train initiatives, organized in the High-Speed Rail Passenger Interstate Compact. Two out-of-state cities, Detroit and Pittsburgh, were selected for Ohio’s share of the network. ORTA estimated the time for completion of the entire project at between thirteen and fifteen years, and estimated the cost at $5.7 billion for the original, Ohio-only network, with an additional $2.5 billion for the optional extensions to Detroit and Pittsburgh ($17 billion and $7.5 billion in 2022).77

Divided over those fifteen-some years, constructing this extended network would cost the state nearly $600 million per annum, before any delays or overruns associated with such an undertaking. In the financial year 1983, Ohio’s overall expenditure amounted to $11.41 billion, already significantly raised from $9.74 billion the previous year.78 The annual cost of the high-speed rail project would have been just shy of—coincidentally—the state’s entire highway fund at around $675 million, or roughly five percent of the overall budget.79 Were there the political will, an additional expense of $600 million per year might not be unusual. From 1979 to 1985, Ohio’s budget nearly doubled from $7.64 billion to $13.06 billion, or by about $904 million more each year. There is, however, one significant problem with this argument: these are nominal figures for annual expenses, and these are the early 80s. Using the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index inflation calculator, measuring in June 1979 Dollars, real overall budgets for Ohio in fact fell from $7.64 billion in 1979 to $7.26 billion in 1982, rising steeply in 1983 to $8.29 billion and settling only at $8.78 billion in 1985.80 These numbers, in other words, do not reveal a state swelling its spending to combat the ongoing recession or even to champion large public works, like a high-speed rail network; they show a state government struggling to tread water in the era of stagflation.

It is in this context that, on Election Day, 1982, Ohioans overwhelmingly voted down a one-percent sales tax increase that would have funded ORTA’s high-speed passenger rail network, with 711,450 in favor and 2,408,254 against. Columbus’s Franklin County voted only slightly more in favor of the issue, at 24.1%.81 Governor Richard Celeste, elected the same night, appointed a task force to continue studying the feasibility of a high-speed network and seek any potential sources of funding.82 It was, it bears repeating, after this electoral failure that ORTA published its Rail Plan Update 1982-83, in which it argued for greater technical requirements and area of service, but it was over. ORTA’s budget was first cut from $4.6 million in 1982 to $1.7 million in 1983, and, by 1984, it was slashed altogether, to zero.83 ORTA was gone, folded into the Ohio Department of Transportation. The next Rail Plan, published by ODOT in 1990, would make no mention of a high-speed plan, nor of any passenger traffic at all, in fact.84

Although similar plans have emerged over the decades since 1983—the High-Speed Passenger Interstate Compact still exists, though under a different name—none would be as ambitious.85 In 2010, as part of the Obama administration’s post-Recession recovery efforts, the Midwest Regional Rail System emerged as a plan to, in essence, do what Ohio and other states had planned to some-thirty years prior. The proposed network would have included roughly the same lines as the 1977 plan, but desired speeds were reduced to 110 miles an hour, if not an even cheaper 79 miles an hour. The plan would have also only entailed improving existing rails, used by slow, unreliably timed freight trains. None of this mattered, however, as Ohio’s Governor Kasich turned down the $400 million in offered federal funds to construct the project.86

Postmortem

So, who did end passenger train service to Columbus? In the most immediate sense, it was Amtrak; they ended the National Limited on September 30, 1979. But that was only after almost a decade of lobbying the federal government for the kind of funding that would have solved most of the problems it faced. Particularly with such a shortage of passenger capacity, the radical cuts to the network it undertook in late-1979 that left Columbus without service could be interpreted as something of an ordered retreat. Amtrak cannot be expected to have materialized ten times the passenger cars it had in its fleet out of thin air. The next best option was to run those 2,000-some cars on a much smaller system. But this only explains why some lines were cut, not why Columbus’s service had to be cut. Even in Ohio, when Amtrak began operations, it was not Columbus but Cleveland that was left out of the network.87 If one of the so-called Three Cs had to lose Amtrak service, it never had to be Columbus, and, at first, wasn’t Columbus. In other words, what made Columbus the city to take such a hit, if one had to be taken?

One might look to Battelle’s construction of the convention center as having ended passenger rail in Columbus. It was the convention center’s construction that demolished Union Station and under Battelle’s management of the project, the promised modernized station was dropped from the plan. Cincinnati and Cleveland still have their original, grand train stations and Columbus does not; it had the “Amshack.” Had Battelle somehow retained Union Station in the plans for the convention center, or had they been able to offer a brand new, intermodal transit hub in the middle of Columbus, Amtrak might have chosen differently.

Perhaps the New York Central bears some blame, too. They cut the Ohio State Limited, connecting the Three Cs, leaving the overall network inherited by Amtrak extremely disjointed—this is what made a trip from Cincinnati to Columbus to Cleveland 1,300 miles long. The passenger lines were burning a hole in the accounts of the private railroads, and only overwhelming sentimentality and the ICC kept these lines running.88 But why did passenger lines perform so badly in the first place? Both the Pennsylvania and the New York Central tried what they could to get people back to riding the train—sleeper coaches for nighttime runs, modern air conditioning, a literal red carpet to board the train at the station—but nothing worked.89 The private railroads competed against air and automobile travel that, again, as Amtrak noted, were both heavily subsidized by the federal government for decades.90 It deserves reiterating, too, that Ohio’s highway spending in 1983, a generally unquestioned expense, was about equal to a year of funding toward the high-speed rail project.

Also among the culprits in the case is of course the federal government. President Carter’s administration pursued a hard line of disinvestment, deregulation, and retreat. Despite the willingness of some in Congress to raise funding for Amtrak, Carter would not sway from downsizing.91 When the first secretary of transportation wasn’t getting on board, he was pushed out in favor of a more committed replacement.92 It was Congress that mandated Amtrak make a profit and it was Congress that refused to fund the high-speed rail project of which Ohio, represented by ORTA, was only one part. Beyond the Carter years, it was the federal government that funded the freeways and incentivized suburbanization, pushing millions into private cars. The dirt roads of the 1930s, too narrow to fit two cars at once, ballooned into four-, six-, eight-lane superhighways ramming through the hearts of cities great and small. This policy decision, along with decades of backing of the airline industry, is a massive, obvious finger tipping the scale against passenger rail, that is only recently, barely being corrected.

Under the Biden administration, Amtrak has announced plans to expand its system over the following decade, including in Ohio, but the network proposed has been restricted to only one new line between Cincinnati and Cleveland, through Columbus and Dayton. Reduced from both the 1977 and 2010 plans, Amtrak’s $2.6 billion ‘3C+D’ project no longer included Akron or Youngstown, and would not connect Columbus directly with Toledo. No mention is made of the planned speed of the route, and even if there were one, Amtrak states that the route would run on track owned by CSX and Norfolk Southern, placing these passenger trains at the mercy of the two freight giants. Amtrak’s plan also expects a frequency of only three round trips per day, down from the 1977 plan’s seven per day on the Cleveland-Cincinnati route.93 Two years since the announcement of the ‘3C+D’ corridor, almost no apparent progress has been made except for renders of Columbus’s new Amtrak station to be built in the basement of the Greater Columbus Convention Center.94 It is the same exact place Battelle was supposed to build its intermodal station, where the final Union Station stood, where the Columbus & Xenia Railroad built its wooden barn one hundred and seventy-three years ago, four hundred feet north of the corner of High and, now, Nationwide.

Eric Rozenman, “Razing of Union Depot likely to continue,” Columbus Citizen-Journal, October 25, 1976; Gerald Tebben, “Depot Arcade Gets Reprieve,” Columbus Dispatch, October 24, 1976.

John Switzer, “Convention Center Near Nuts, Bolts Stage,” Columbus Dispatch, October 24, 1976.

Rozenman, “Razing of Union Depot likely to continue.”

Tebben, “Depot Arcade Gets Reprieve.”

Tebben, “Depot Arcade Gets Reprieve.”

Rozenman, “Razing of Union Depot likely to continue.”

Joe Gillette, “Old friend bids city farewell,” Columbus Citizen-Journal, April 30, 1977.

Switzer, “Convention Center Near Nuts, Bolts Stage.”

Melissa Widner, “‘National Limited’ Takes Last Journey Through Columbus,” Columbus Dispatch, October 1, 1979.

Jeffrey Darbee, “Union Station: Who Was First?” in Indianapolis Union and Belt Railroads (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2017), 55.

Chester Winter, A Concise History of Columbus, Ohio and Franklin County (Bloomington: Xlibris, 2009), 54.

Darbee, “Union Station: Who Was First?” 55.

Winter, A Concise History of Columbus, 54.

Edward H. Miller, The Hocking Valley Railway (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2007), 20.

Warren Van Tine, A History of Labor in Columbus, Ohio: 1912-1992 (Columbus: Center for Labor Research, 1993), link, 16-17.

Ohio General Assembly, Executive Documents: Message and Annual Reports for 1868 Made to the Fifty-Eighth General Assembly of the State of Ohio at its Adjourned Session Begun and Held in the City of Columbus, November 23, 1867 (Columbus Printing Company, 1869), link, 202.

Winter, A Concise History of Columbus 55.

“Union Depot No. 2: 1891 Trestle Construction,” Columbus Railroads, accessed November 26, 2022, link.

“CUS Complex: Freight House Row circa 1946,” Columbus Railroads, accessed November 26, 2022, link.

“Spruce Street: Olentangy River Looking Northeast circa 1950,” Columbus Railroads, accessed November 27, 2022, link.

US Department of Commerce, Census of Population: 1950, vol. 2, Characteristics of the Population, part 35, Ohio (US Government Printing Office, 1953), link.

Van Tine, A History of Labor in Columbus, Ohio, 16.

Office of Highway Policy Information, “Motor-Vehicle Registrations, by States, 1900-1995,” in Highway Statistics Summary to 1995 (US Government Printing Office, 1995), link.

Ohio Department of Highways and Public Works, Report of a Survey of Transportation on the State Highway System of Ohio (1927), 73-76.

Ohio Department of Highways and Public Works, Report of a Survey, 19.

Ohio Department of Highways and Public Works, Report of a Survey, 73.

“Rail Transportation History.”

“National Interstate and Defense Highways Act (1956),” National Archives, accessed November 28, 2022, link.

Ohio Department of Highways, 4-Year Report to the Governor: 1959-1962 (1962), 41.

“Outerbelt Finish Set for Aug. 20.” Columbus Dispatch, July 9, 1975.

Kern and Wilson, Ohio: A History of the Buckeye State (Chichester, UK: Wilson-Blackwell, 2014), 407; US Department of Commerce, Census of Population: 1950, 168; US Department of Commerce, Census of Population: 1970, vol. 1, Characteristics of the Population, part 37, Ohio (US Government Printing Office, 1973), 31.

Kern and Wilson, Ohio: A History of the Buckeye State (Chichester, UK: Wilson-Blackwell, 2014), 407; US Department of Commerce, Census of Population: 1950, 168; US Department of Commerce, Census of Population: 1970, vol. 1, Characteristics of the Population, part 37, Ohio (US Government Printing Office, 1973), 31.

Marc Levinson, The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the Economy Bigger, 2nd ed. (Princeton University Press, 2016), 205-214.

Rush Loving Jr., The Men Who Loved Trains: The Story of Men who Battled Greed to Save an Ailing Industry (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006), 15.

Mike Schafer and Joe Welsh, Classic American Streamliners (Osceola, WI: Motorbooks International, 1997), link, 31-32.

Loving Jr., The Men Who Loved Trains, 55.

Loving Jr., The Men Who Loved Trains, 50.

Loving Jr., The Men Who Loved Trains, 95-115.

“Convention Center Pact Approved,” Columbus Dispatch, April 4, 1972.

Ed Lentz, “As It Were: John Gordon Battelle proved his mettle here,” Columbus Dispatch, July 26, 2019, link.

“Battelle’s world: Columbus-Based research giant extends its global reach,” Columbus Dispatch, January 24, 2009, link.

Robert Ruth and Robert Sohovich, “Sizing Up The Center: Convention center controversies have swirled around how big to build it,” Columbus Dispatch, February 5, 1989.

Robert Horan, “City Convention Center Definite, But…” Columbus Dispatch, July 6, 1969.

Horan, “City Convention Center Definite”.

“Convention Center Pact Approved”; Herbert Cook, “Convention Center Bond Issue Recommended,” Columbus Evening Dispatch, May 18, 1971; Horan, “City Convention Center Definite.”

“6 Years Later, Ground Not Broken for Center,” Columbus Dispatch, July 31, 1977; Ruth and Sohovich, “Sizing Up The Center.”

Ruth and Sohovich, “Sizing Up The Center”; Eisenman is likely much more known for his design of the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, perhaps better known simply as the Berlin Holocaust Memorial.

“New Rail System Begins Operation,” Columbus Evening Dispatch, May 1, 1971.

Background on Amtrak (Washington: Amtrak, 1978), 6-11.

Phil Primack, “Amtrak’s Big Talent: Killing Needed Trains,” Washington Post, December 23, 1979, link.

Background on Amtrak, 28-30.

Primack, “Amtrak’s Big Talent.”

Primack, “Amtrak’s Big Talent.”

Primack, “Amtrak’s Big Talent”; Widner, “‘National Limited’ Takes Last Journey.”

Comptroller General of the United States, Should AMTRAK’s Highly Unprofitable Routes Be Discontinued? (US General Accounting Office, 1978), 23.

Schafer and Welsh, Classic American Streamliners, 31-32.

Peter Lynch, Penn Central Railroad (St. Paul: MBI, 2004), 32.

“New Rail System Begins Operation,” Columbus Evening Dispatch, May 1, 1971.

Ohio Rail Transportation Authority, Ohio High Speed Intercity Rail Passenger Plan (Phase 1) (Cleveland: Howard, Needles, Tammen & Bergendoff, 1977), 30.

Ohio Rail Transportation Authority, RailOhio: The Ohio Rail Plan 1978-79 (1978), 20.

Comptroller General of the United States, Should Amtrak Develop High-Speed Corridor Service Outside the Northeast? (US General Accounting Office, 1978), 31.

Comptroller General of the United States, Should AMTRAK’s Highly Unprofitable Routes Be Discontinued? 5.

Amtrak Fiscal Year 1980 Authorization and Amtrak Route Restructuring, Before the Subcommittee on Transportation and Commerce, 96th Cong. 269-294 (1979) (statement of Nat Simons, Jr., Executive Director of the Ohio Rail Transportation Authority), 271-272.

A bill to amend section 403(b) of the Rail Passenger Service Act, HR 3064m 96th Cong. (1979).

Amtrak Fiscal Year 1980 Authorization and Amtrak Route Restructuring, 288.

William Vantuono, “Staggers at 40: A Rail Market ‘Allowed to Work Where Competition Exists’ (UPDATED),” Railway Age, October 14, 2020, link.

Amtrak Fiscal Year 1980 Authorization and Amtrak Route Restructuring, 270-276.

Ken Ringle, “The Seduction of Brock Adams,” Washington Post, March 22, 1992, www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1992/03/22/the-seduction-of-brock-adams/8f00f4f4-45ef-4594-951b-a382d70213f3/.

Ohio Rail Transportation Authority, Ohio State Rail Plan Update 1982-83 (1983), 7.

Ohio Rail Transportation Authority, RailOhio: The Ohio Rail Plan 1978-79, 21-22.

Ohio Rail Transportation Authority, Ohio State Rail Plan Update 1982-83, 7-10.

Ohio Auditor of State, 1982 State of Ohio Annual Report (Columbus: Ohio Auditor of State, 1982) 288; Ohio Treasurer of State, Annual Report of the Treasurer of State to the Governor of the State of Ohio for the Fiscal Year July 1, 1982 to June 30, 1983 (Columbus: Ohio Treasurer of State, 1984) 1.

Ohio Treasurer of State, 1983 Annual Report, 1.

Ohio Auditor of State, 1982 State of Ohio Annual Report, 288; Ohio Treasurer of State, 1983 Annual Report, 1; Ohio Treasurer of State, 1984 Annual Report: Fiscal Year July 1, 1983 to June 30, 1984 (Columbus: Ohio Treasurer of State, 1985) 1; Ohio Treasurer of State, 1985 Annual Report (Columbus: Ohio Treasurer of State, 1986) 10.

“Election Results,” Columbus Dispatch, November 3, 1982.

Transmode Incorporated, “I Introduction,” in Market Analysis of High Speed Rail Services in Ohio: Submitted to Ohio Department of Transportation (Arlington, VA: Transmode Incorporated, 1985) 1.

Ohio Treasurer of State, 1983 Annual Report, 21; Ohio Treasurer of State, 1984 Annual Report, 23.

Ohio Department of Transportation, Ohio State Rail Plan 1990-91, (1990).

National Center for Interstate Compacts, “Interstate High Speed Rail Network Compact,” Council of State Governments, accessed November 16, 2022, link.

Texas High Speed Rail, “U.S. System Summary: OHIO HUB,” Texas Department of Transportation, accessed November 17, 2022, link.

“New Rail System Begins Operation,” Columbus Evening Dispatch, May 1, 1971.

Rush Loving Jr., The Men Who Loved Trains, 122-123.

Schafer and Welsh, Classic American Streamliners, 31-32.

Amtrak, Background on Amtrak (Washington: Amtrak, 1978).

Phil Primack, “Amtrak’s Big Talent.”

Ken Ringle, “The Seduction of Brock Adams.”

Amtrak, “3C+D Corridor: Amtrak’s vision to connect communities across Ohio,” Amtrak, accessed November 17, 2022, www.amtrakconnectsus.com/maps/cleveland-columbus-cincinnati/; Ohio Rail Transportation Authority, Ohio High Speed Intercity Rail Passenger Plan (Phase 1), 19.

Brent Warren, “Study: Amtrak Station, New Plaza Could be Added to Convention Center,” Columbus Underground, January 11, 2022, https://columbusunderground.com/study-amtrak-station-new-plaza-could-be-added-to-convention-center-bw1/.